Image

By James A. T. Lancaster, The University of Queensland

The Christmas tree is a modern invention. It is a largely secular symbol, having no basis in the Bible. There are many trees in the Bible, from the Tree of Knowledge and the Tree of Life in Genesis to the reference to Christ’s cross as a “tree” in Acts. But there is no Christmas tree.

The same is true of ancient, pagan sources. While it might be tempting to draw connections between the Christmas tree and pagan gods and festivals, such as the Egyptian god Ra and the Roman festival Saturnalia, the Christmas tree as we know it is completely unrelated.

The same goes for the legend of Saint Boniface and the Germans, which is just that: a legend. Almost all religions, ancient and modern, have used trees in their rituals, but not Christmas trees.

Even when we get to the 16th century, the Christmas tree we are familiar with is still 350 years in the future.

The story of Martin Luther, to whom the origins of the tree have been popularly attributed, is not supported by scholarship. As wholesome as it sounds, Luther was not overwhelmed by the beauty of a snow-covered tree while contemplating the infant Christ.

The truth is the Christmas tree is a relatively new tradition. It originated as a minor, localised tradition in the 17th century in a single place: the Alsatian capital of Strasbourg.

German citizens of Strasbourg included a tree as part of a judgement tradition on Christmas day. Children would be judged by their parents. If good, bonbons would be left under a tree. If bad, there would be no bonbons – a hint of what was to come on Judgement Day.

The ritual spread to other parts of Germany in the 1770s. The German romantic novelist Goethe offered the first account of the Christmas tree to reach a wide audience in Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). But it wasn’t widely adopted in Germany until the 1830s, after the Christmas tree began to gain popularity in America.

The tradition came to Britain in the 1830s, introduced by German merchants in Manchester around the same time the courts of George III and William IV, themselves of German descent, introduced it to British aristocracy.

Queen Victoria and Prince Albert popularised the tradition in Britain, when Albert set up a Christmas tree at Windsor in 1840.

The scene was immortalised in The Illustrated London News in 1848, when an engraving was printed showing Victoria, Albert and their children around a candlelit tree with glass ornaments.

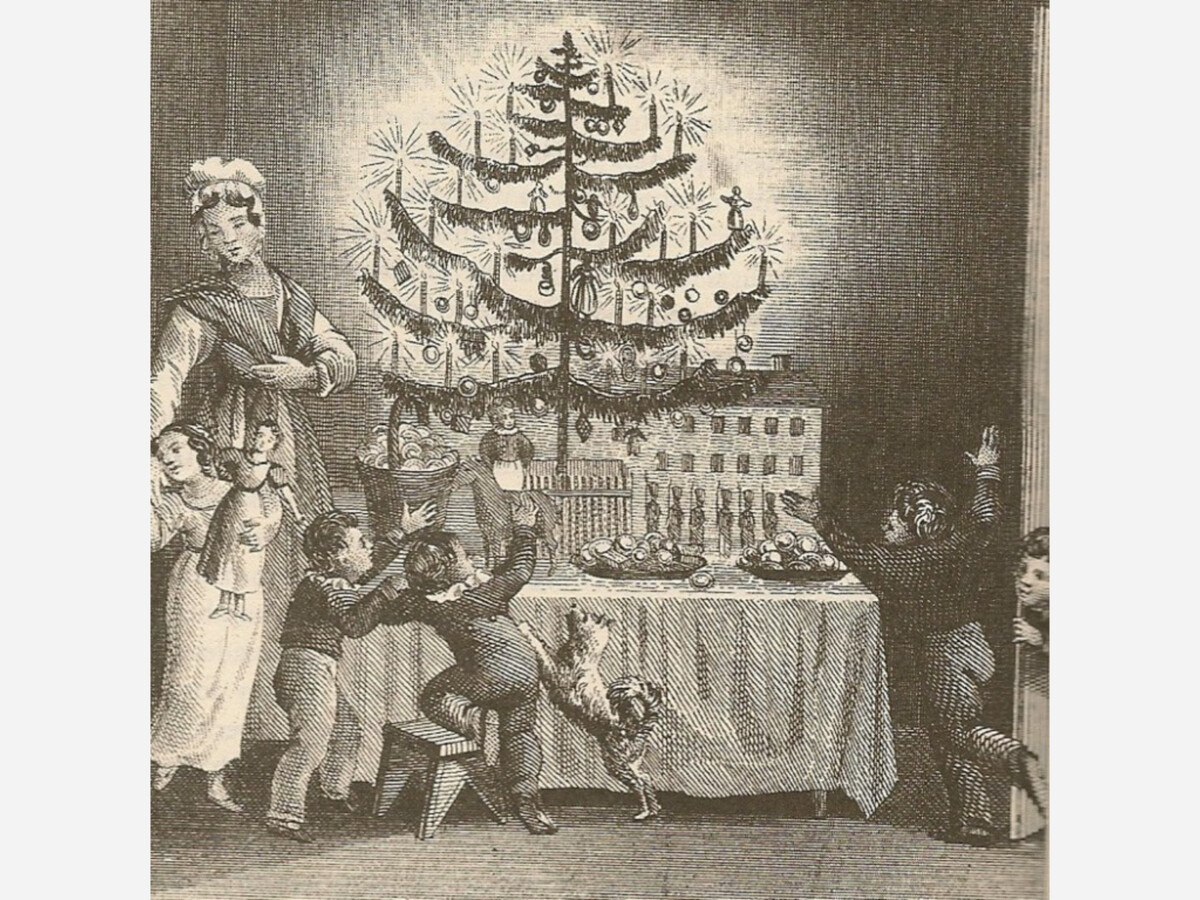

"The Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle" by Joseph Lionel Williams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. This image depicts Victoria and Albert's Christmas tree.

"The Christmas Tree at Windsor Castle" by Joseph Lionel Williams, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons. This image depicts Victoria and Albert's Christmas tree.The Christmas tree with gifts hidden under its boughs is derived from America, first introduced in Pennsylvania as early as 1812.

The Christmas tree was adopted into American culture as an attempt to remove the gross debauchery of the season.

Before the middle of the 19th century, Christmas was celebrated as a carnival, in which revellers – usually the poor and working classes – would parade around towns, knocking on the doors of the wealthy and demanding to be feasted or given drink. This practice, “wassailing”, evolved to involve drunkenness, vandalism and lewd acts.

The rowdiness of the Christmas season was to be mitigated by the indoor, child-friendly Christmas tree around which the middle-class family would gather.

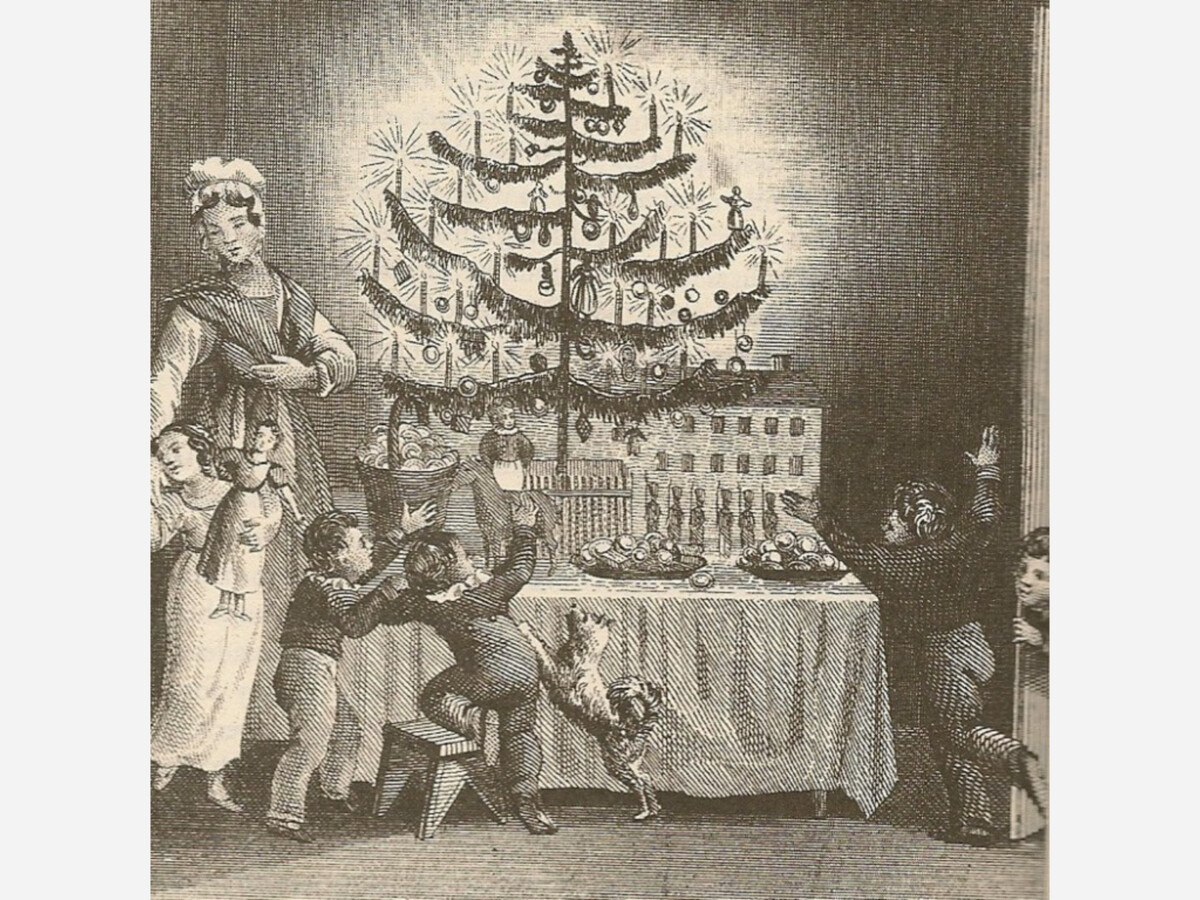

"The Christmas Tree" by Winslow Homer, Public domain via Smithsonian. The child-friendly Christmas tree was depicted in 1858.

"The Christmas Tree" by Winslow Homer, Public domain via Smithsonian. The child-friendly Christmas tree was depicted in 1858.Children would no longer be permitted outside to revel in the season. The outside would be brought inside: a tree cut down and brought indoors so Christmas could ensue in the safety and comfort of the home.

Adopted to mitigate the excesses of the season, American merchants and manufacturers popularised the Christmas tree. Presents were not placed under the tree until savvy manufacturers recognised the potential of the new indoor festivities.

The gross overindulgence of Christmases past – drinking, feasting and sex – made a comeback in a new, middle-class way with the giving of gifts.

The gift-wrapped Christmas present is an American invention of the 1840s that took the world by storm. Wrapped gifts began to be placed under trees by parents in response to the marketing strategies of book publishers.

American families learned about the new tradition not from German immigrants, but from these exact books: books in which the Christmas tree was depicted as a means to keep children happily indoors with what essentially amounts to a bribe. What better way to convince your children to stay inside, away from the revelry and out of trouble, than leave gifts under the tree?

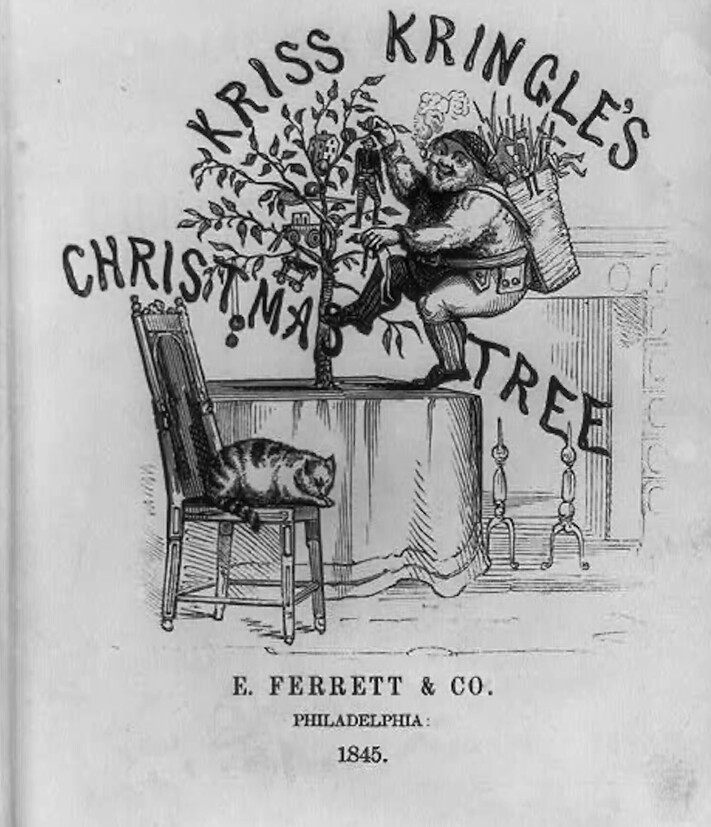

Booksellers published collections of short stories and poems, such as Kriss Kringle’s Christmas Tree (1845), in which children received presents of books, but also swords, drums or dolls.

Image in Public Domain from Library of Congress via picryl. In Kris Kringle's Christmas tree, children were presented with presents under the tree.

Image in Public Domain from Library of Congress via picryl. In Kris Kringle's Christmas tree, children were presented with presents under the tree.The genius of the book publishers was to present the new scheme of purchasing gifts for children as an old “folk tradition”. Parents were led to believe placing gifts under the Christmas tree was a ritual as old as the biblical Magi, with their gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh.

Despite its name, the modern Christmas tree has little connection to an imagined Christian past.

From the 1830s when it became a widespread, middle-class ritual to bring a tree indoors and decorate it with lights, ornaments, angels and stars, the Christmas tree has been a largely secular symbol of the season, whose success remains tied to the forces of a consumerist economy.

James A. T. Lancaster, Lecturer in Studies in Western Religious Traditions, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.